In the late 1990s, Dr. Ed Wagner (and his team at the Macccoll Center – now the ACT Center), created the Chronic Care Model for the delivery of care. They had the support of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

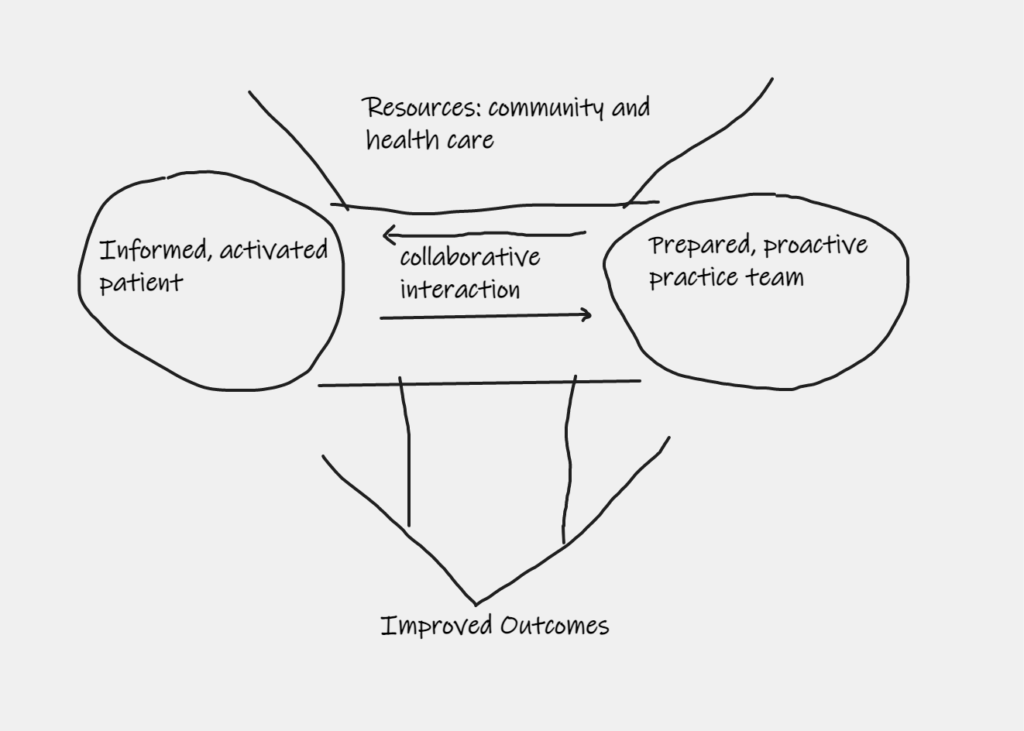

The chronic care model recognizes that when care is delivered over time, patient involvement becomes increasingly important. The key to good outcomes is collaboration between an informed, activated patient and a prepared, proactive practice team. As community and health care resources are brought to bear, their availability and implementation (or non-implimentation) should be discussed as shown below with the goal of improved outcomes.

One of the problems with the Chronic Care Model was (and is) finding “informed” and “activated patients. Dr. Wagner’s team realized self-management support, including education and tools, was an essential feature because most patients lack the training and experience necessary to empower them as a member of the care team. That is why a key change concept was emphasis of the patient’s central role in managing his or her own health. This is particularly important in treatment of chronic conditions such as diabetes; providers see patients irregularly, but day to day management of the condition is essential to good outcomes.

Further, absence of if a medical home (preferably someone who has or can provide whole person knowledge regarding the patient’s circumstances), can impair the practice team’s ability to be “prepared” The absence of continuity of care or coordination of care can impair the team’s ability to be prepared, or remain prepared over time. As patients see more providers with no history regarding the patient’s circumstances, reliane on the medical record becomes more important; any error in the medical record can lead to compounded problems as providers unaware of documentation errors rely on the record.

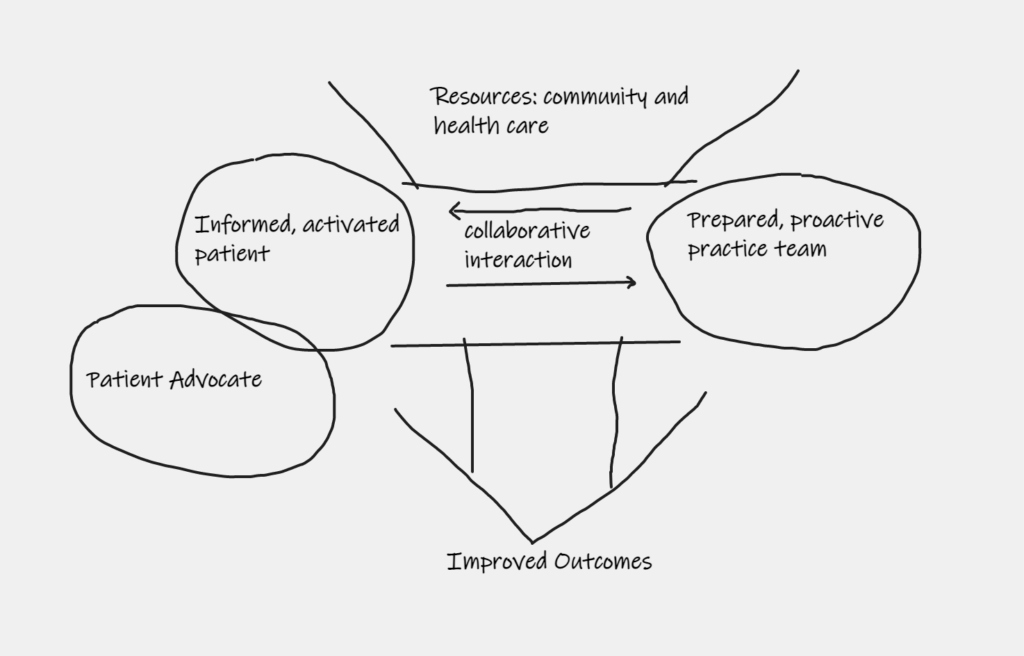

One way to address these potential issues is with patient advocacy as shown below.

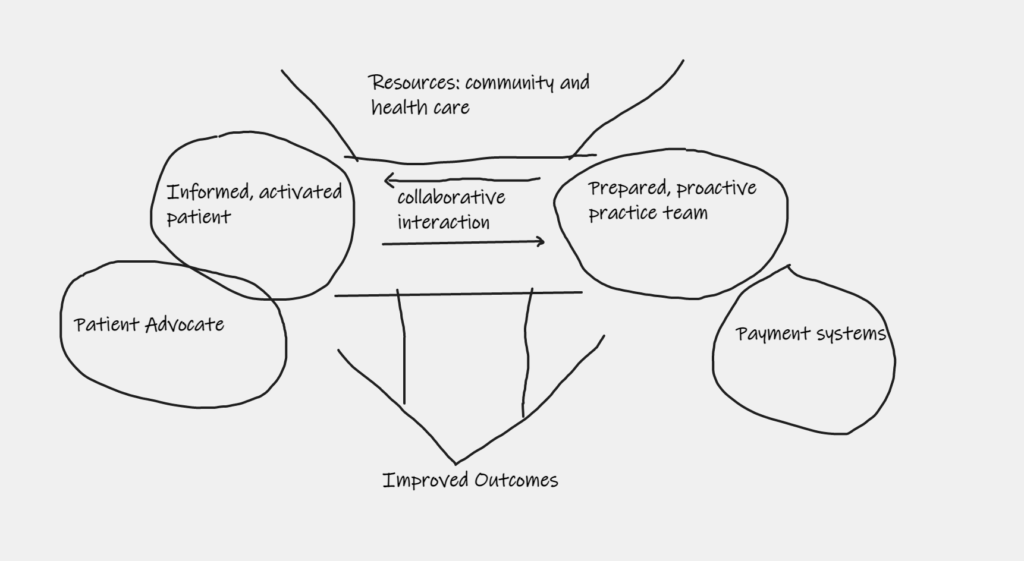

Patient advocates are not health care decision-makers and frequently have general or limited medical knowledge. They can assume different roles. First, a patient advocate might be a second set of eyes and ears as mom or dad visit the doctor. Patient advocates might be keepers of the medical journal or records. They might be individuals who check to be certain medications were taken at the rights times and in the right amounts. Next, patient advocates might educate decision-makers regarding rights to health information. They might provide information regarding the use of advance directives, how the informed consent process works, and the riht to choose among treatment options after receiving information. They might provide information regarding the right to refuse treatment. Advocates might also assist patients and health agents understand their rights concerning payment sources, such as insurance, Medicare and Medicaid. That pont leads to another problem illustrated as follows:

in 1929, a group of school teahers in Dallas contracted with Baylor Univerity. They would receive up to 21 days of inpatient hospital care per year in return for a monthly payment of 50 cents. By 1937, there were 26 plans similar to this with 600,000 members. They formed the networks that would become Blue Cross and Blue Shield.

Since development of the “Big Blues,” third-party payment (TPP) of health care expense has been the norm rather than the exception. Since passage of the Medicare and Medicaid Acts in 1965, many people no longer believe they should have to pay for their own care. Unfortunately, a more insidious problem can exist. People, including health care providers, are often loyal to the person who pays them. TPP sources have a financial motivation to minimize expenses. TPP’s might deny payment for certain treatments, which could have the effect of causing health care providers to suggest treatment options that get them paid rather the the option best for the patient. Recognition of this problem lead to formation of the Life Care Planning Law Firms Association. For purposes of this post, the important take-aways are these:

- Information is a key compontent in making good decisions and for good outcomes. Unfortunately, patients and health agents begin the process not knowing what they don’t know. Since they lack information necessary to even ask the right questions, patients and health agents need education and training from providers and if they don’t get it, need an advocate is necessary who can ask the right questions.

- Don’t give up. Keep asking questions until information is provided. Get an advocate involved if necessary, but don’t give up.

- Don’t forget that treatment options being offered might be limited to those covered by TPP. If you can afford to pay for your own care, there miht be other care options. For example, if you don’t want to go to a nursing home and you can afford to fund your care at home, then there’s no rule saying you have to go to a nursing home. You’re allowed to pay your own way and get any (legal) option available.